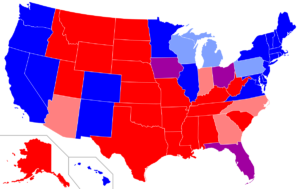

Courtesy Wikipedia

Everybody knows that the United States is a highly polarized country, divided into blue states and red. Blue states tend to favor minority voting, abortion rights, mask mandates, climate mitigation, gay and transgender rights, Medicare expansion, gun controls, a higher minimum wage, more ample state entitlements, and a church/state divide, among other policies. Red states just the opposite. Moreover, individuals who identify as blue or red often do not get along, to put it mildly (this is technically known as ‘affective polarization’).

This is far from the first time in American history that the country has faced polarization. In the middle of the 19th century, it took a civil war to (at least temporarily) resolve our economic and cultural differences. More lives were lost in that war than any other the United States has fought. And more episodes of polarization have broken out since then. Now, far-fetched as it might seem, some people are once again raising the specter of an American civil war.

Although this situation continues to cause a great deal of hand-wringing few remedies, if any, have gained much traction. There is a way out of this dilemma, however, but it requires neither side to win.

The recent rise of polarization is largely due to the growth of direct rule – that is, the power of the central government and Supreme Court – which from the 1960’s onward has tended to advance the (mostly) cultural preferences of the residents of the blue states of the Union at the expense of their red state counterparts. The aggressive reaction of the supposed losers, first seeing the light of day in Pat Buchanan’s 1992 unsuccessful presidential campaign, is a consequence of heightened direct rule. When direct rule advances in a multicultural polity, it’s likely to cause a backlash from culturally-distinct elites who fear displacement and delegitimation (Hechter 2000; 2004). These elites seek to mobilize their followers in opposition.

What is to be done? The answer is to adopt greater indirect rule – that is, to allow the voters in both blue and red states to assume more governance of their territories at the expense of the power of the central (Federal) government (Mueller and Hechter 2021; Perrings et al. 2021). Now, to some extent, the respective powers of the Federal government and the states are constitutionally limited (Watts and Vigneualt 2000). Despite this, however, a significant amount of regional redistribution occurs. Constitutionally, therefore, the American system allows for considerable state sovereignty with respect to policy. The proposed reform would seek to minimize such intergovernmental transfers.

The argument of this proposal therefore takes a decidedly Madisonian rather than Hamiltonian view of American governance. Blue states would probably remain largely socially liberal, pro-regulation, and more redistributive, whereas red ones would become more socially conservative, xenophobic and libertarian. The bottom line is that the majority of voters in each type of state would be more satisfied because they would have enhanced self-governance.

As time goes on, blue and red states would come to diverge ever more economically and culturally. Just how they would ultimately fare would be unknown at the outset. What is likely, however, is that some of the political minorities in each type of state might be induced to vote with their feet, and therefore rates of geographic resorting would increase. At the same time, the different fates of the two kinds of states would permit everyone to see which type of governance they would prefer.

As Barry Weingast (1995) has argued, greater indirect rule would act as a natural experiment to assess the relative merits of the various types of regimes. Just as Ronald Reagan challenged the USSR to keep up with American military expenditures – a challenge that the USSR could not meet — so the blue and red states would challenge one another with respect to effective governance. Since this arrangement would heighten self-governance throughout the country, affective polarization would no longer have much of a leg to stand on.

References

Hechter, Michael. 2000. Containing Nationalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hechter, Michael. (2004). “From Class to Culture.” American Journal of Sociology 110(2): 400-445.

Mueller, Sean and Michael Hechter. 2021. “Centralization through Decentralization? The Crystallization of Social Order in the European Union.” Territory, Politics, Governance: 9:1 (2021), 133-152

Perrings, Charles, Michael Hechter, and Robert Mamada. 2021. “National Polarization and International Agreements.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 118, e2102145118.

Watts, Ronald L. and Marianne Vigneault. 2000. “Fiscal Federalism in the United States.” Working Paper, Watts Institute for Intergovernmental Relations, Queens University, Canada.

Weingast, Barry R. (1995). “The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-3.

0 Comments