It is possible to find coverage of most things and nationalism in academic journals. For example: obscure sports (lacrosse) (Robidoux, 2022), wildflowers (Dahl, 1998), style of hats (Akturk, 2017) and food: gastronationalism (De Soucey, 2010) – literally, nationalism and chips. And a hunt in a university library catalogue does produce hits for the terms ‘nationalism’ and ‘crime’. The articles identified are similar in subject matter to those obtained through a general Google: war crimes (documented atrocities, sometimes extending in scale to alleged genocide) carried out by states in the name of nation (for instance, Kelly, 2017). The response of the accused to the accusation is rarely, ‘So what, they deserved it, they are our enemies’. This does happen. Witness the second phase comebacks of prominent Israeli figures (for instance, that of Interior Minister, Ayelet Shaked, and former West Bank military prosecutor, Maurice Hirsch) to the killing of Shireen Abu Akleh. But the rebuttal is usually more one of denial with the counter allegation that 1) the evidence was fabricated to discredit us; 2) crimes against our own nationals are ignored; and/or 3) we only did to them what they did to us (Cohen, 2001). All three sentiments are there in Russian retorts to Western reports of the atrocities committed by its troops in Ukraine.

An important subject though this is, I am less interested in this relationship (by any legal or moral register, wrongdoing in the name of nation) than other aspects. It is one that I first became aware of in the 1990s when I got to know a number of people from former Yugoslavia who’d come to Britain, and subsequently, through a relationship, regularly travelled to the region. Objective accounts were rare but listening between the lines a dominant theme was how the conflict had been used as a chance to make money. Typically, this would be through stories about, say, a guy who’d run a couple of dodgy bars and clubs in the FRY who became a regional Croat war lord. Always with a Savonia pin on the lapel of his Italian suit, he’d led the looting in the neighbourhood ethnic cleansing before becoming involved in stolen car rackets that went to the top of the HDZ – his own four-wheel drive purchased from diaspora donations intended to rebuild the parish Catholic church. Or the former Serbian football ultra, turned macho Chetnik fighter, reputed to have carried out killings in Vukovar, more recently making money from cigarette and people smuggling through the Balkans. It didn’t take long once the fighting stopped for ethnic enmities to be put aside for the sake of mutual criminal gain through limited, networked co-operation.

This angle on the breakup of Yugoslavia did get some coverage. Tim Judah, a journalist who spent time on the ground, devoted a whole chapter on the wars as an opportunity for financial gain in his book, The Serbs (1997). Other writers (Drakulić, 2004) emphasized the role of lasting community omerta over who’d benefited from the spoils of war. Within the literature on organised crime, recent accounts emphasize that it is impossible to distinguish between criminal and political violence because states and other non-state armed groups form strategic relationships with criminal organisations to help them defeat common enemies whilst gaining access to resources and illicit markets, as well as trafficking routes (Barnes, 2017: p. 969). But for the most part the criminal aspect in the break-up of Yugoslavia in particular, and nationalist conflicts more widely, have not featured in academic accounts.

There is good reason for this. Whatever one’s understanding of the rise of nations and nationalism, crime, defined simply as action or omission that breaks the law, seems a different and unrelated activity. There are accounts of nation building that stress that crime was functional to states as they sort legitimation and a monopoly on the use of physical violence (Anter, 2020). But a cornerstone of crime, specifically organised crime, is that it is a self-interested activity of an individual and/or group. Crime concerns private benefit, not acquisition for a wider constituency or ideology. Further, definitions of organised crime usually emphasize the ruthless pragmatism of participants (Abadinsky, 2017). Interpersonal ethics of respect and loyalty that secure degrees of trust may be lauded but are secondary to the real-world business of making money every which way – ‘just business with the gloves off’ in the words of a character in a Jack Arnott novel, The Long Firm. So the selfish, limited, avaricious nature of crime seems rather different from the stuff of nations and nationalism – something that is reflected in the academic lacuna. The following connections, drawn from a perusal of writing on, the one hand, particular nationalisms, and, on the other, organised crime, indicate that there is indeed a relationship between the two subjects.

The first is the use by national liberation movements of criminality for fund raising purposes (in part, why their opponents dismiss them as terrorists or simply criminals). Examples include the high jacking of ships, arms smuggling, extortion, money laundering, passport forgery, cyber-attacks and credit card fraud by the Tamil Tigers of Eelam from 1994 to 2010 (Hutchinson and O’Mally, 2007). The Tigers were militarily crushed by the Sri Lankan army in 2009, but one suspects some of their cadre enjoy a criminal afterlife. The Irish Republican Army was publicly vehemently opposed to illegal drugs during the years of armed struggle in Northern Ireland and England, 1970-1997, to the extent of knee capping street dealers. However, it was known in 1980’s and 90s Dublin that the IRA sought control of drugs dealing under the cover of vigilante action against addicts (Cusack 1996; Tupman, 1998). One of the issues in conflict resolution following the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 has been the increased involvement of paramilitary groups, loyalist and republican, in organised crime – although, typically, some figures have become legitimate businessmen (Jupp and Garrod, 2019). Some proscribed nationalist parties, unable to raise funds legally, are important to criminal supply lines. The Kurdish Workers Party has been a key player in the flow of drugs through the Eastern Balkans since the 1980s, a route for 80 per cent of Europe’s narcotic intake (Roth and Sever, 2007).

The obvious objection to this is that there is nothing specific about nationalist parties and crime. The point is valid. In some cases ostensibly respectable political parties are little more than criminal outfits. For instance, The Socialist Party never won more than 15 per cent of the popular vote in post war Italy, but wielded coalition making parliamentary power – between 1983-1987 with Bettino Craxi as prime minister (Economist, 2000: p. 52). It was common knowledge that it was basically a mafia front. What is important in relation to our subject is a merger of nationalist and criminal imagery and regalia. For instance, the romantic figure of the rebel in Irish republican mythology bled into the feared gangster hard man during the years of ‘the troubles’ (Silke, 1999).

A second inter connection is between criminality and nationalism in a populist guise through the creation of mafia states. The ‘mafia state’ tag is well known – and is not just invective. It features in the titles of books about contemporary Russia and Hungary (Harding, 2012; Magyar, 2016). The machinations are most apparent in states where there was formally a semblance of liberal democracy with autonomous institutions to be captured and corrupted by the ruler and his – and it is invariably ‘his’ – party. There are several aspects to this process of criminalisation.

Writers don’t altogether agree, but a dominant theme in criminology is the hierarchal structure of the criminal syndicate, based on connections of family, clan (party) and original locality (for discussion see Wright, 2005: pp. 1-21). Ritualised displays of power and fealty are intrinsic to this mode of organisation. Take the choreographed meeting between Vladimir Putin and his national security council just days before the invasion of Ukraine, in which ministers had to publicly declare their loyalty to the boss. Without the cameras, the scene could have come from The Sopranos. Then there is the systematic seizure of the organs of state, the media and key sections of the national economy by the ruling party – institutionalised corruption through clientelism – and crucially the cowing of the independence of judiciaries. The net result is vast fortunes for the favoured few, ostentatiously displayed. Whilst largesse through the distribution of benefits secures patronage, intimidation by the threat and reality of violence is an ever present. Nationalism – a certain projection of nation – features as an ideological monopoly of the regime in this context. The president, henchmen and his media outlets can decree who belong as true patriots – members of the gang/people – whilst stigmatising designated enemies as working to the agenda of a foreign power or a malign global conspiracy. This results in, variously, degrees of paranoia, emotional investment in a leader as the strong man who, despite blemishes, has the nation’s interests at heart, but conversely for many the retreat from any engagement in politics, i.e. widespread apathy.

None of this means that nationalist leaders involved are themselves genuine patriots. Balint Magyar (2016) depicts Viktor Orbán as a cynical pragmatist, concerned only in the bolstering of his ego and financial gain, ever ready to denounce the EU whilst taking its subsidies. Even figures in the Conservative Party say that the only constant with the British prime minister, Boris Johnson, a politician who gained power by opportunistically pledging to ’get BREXIT done’, is his own self-interest. As is well known, there were more breaches of Covid lock down laws at 10 Downing Street than at any other address in the country. Simultaneously pandemic contracts worth tens of millions were awarded to the firms of Tory donors (Good Law Project, 2021). Subsequently, the Johnson government has moved on to threaten to illegally break its own leaving agreement with the EU and flout UN conventions on the right to asylum – the latter, probably more motivated by a desire to appeal to anti-immigrant sentiment than end people smuggling. Notoriously, Russia’s kleptocracy spend their riches outside Russia (now in the UEA rather than London – Kerr, 2022), educate their children abroad and so on.

As populist nationalists criminalise so they draw organised criminals into their regime. A good illustration is the way in which the Night Wolves Motorcycle Club transitioned from ‘outlaw’ bikers in 1990s Russia, making money from drugs and protection, to a legal, state funded and wildly nationalistic paramilitary organisation under Putin since 2000, active in the Donbas and elsewhere (Harris, 2020). Pictures of Putin riding his Harley with the boys are easily found.

A final cross over between crime and nationalism is less covered in criminology: the allure of the gangster figure – accounting in part for popular fascination with crime – and populist leader. In part, this stems from a similar propensity to treat standard conventions with contempt, to thumb their nose at rules and authority because they just don’t care and know they can get away with it time after time – to depart from both tradition and bureacracy in Weber’s (1968) depiction of the charismatic leader. Here, Trump, Bolsonaro and Modi are the obvious examples.

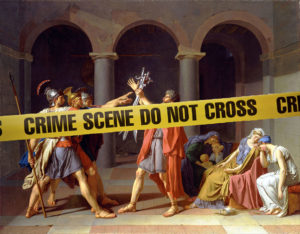

What implications do these points have for the study of nations and nationalism? Well, obviously they don’t mean that all nationalist leaders should be treated as Godfather figures, all national movements as akin to criminal rackets. However, there can seem a tendency in academic discussions to treat the subject with an undue reverence, even when writers initially note that nationalism takes both positive and negative forms. Recognising the overtly criminal aspects of the phenomenon should serve to underline the latter.

Dr Sam Pryke is Senior Lecturer in Sociology in the Faculty of Social Science and Arts at Wolverhampton University

References

Abadinsky, H. (2017). Organized Crime. Australia: Cengage Learning.

Akturk, A.S. (2017). ‘Fez, Brimmed Hat, and Kum û Destmal: Evolution of Kurdish National Identity from the Late Ottoman Empire to Modern Turkey and Syria’, Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association 4, 1: 157–87. https://doi.org/10.2979/jottturstuass.4.1.09

Anter, A. (2020). ‘The Modern State and Its Monopoly on Violence’ in Hanke, E.; Scaff, L; Whimster, S. (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Max Weber. Oxford: University Press.

Barnes, N. (2017). ‘Criminal Politics: An Integrated Approach to the Study of Organized Crime, Politics, and Violence’, Perspectives on Politics 15, 4: 967–87. DOI:10.1017/S1537592717002110

Cohen, S. (2001). States of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering. Oxford: Wiley.

Cusack, J. (1996) ‘IRA linked to Dublin drug attacks’, The Irish Times, May 31st. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ira-linked-to-dublin-drug-attacks-1.54102

Dahl, G. (1998). ‘Wildflowers, Nationalism and the Swedish Law of Commons’, Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology 2, 3: 281–302.

De Soucey, M. (2010). ‘Gastronationalism’, American Sociological Review 75, 3: 432–55, DOI:10.1177/0003122410372226

Economist, The (2000) ‘Addio, Craxi, Symbol of a Rotten Era’, January 20th, 354, 8154: 52

Drakulic, S. (2004). They Would Never Hurt A Fly: War Criminals on Trial in the Hague.

London: Abacus.

Good Law Project. 2022. ‘LEAKED: The Conservative politicians who referred companies to the PPE “VIP lane”’. https://goodlawproject.org/news/conservative-politicians-vip-lane/

Harding, L. (2012) Mafia State: How One Reporter Became an Enemy of the Brutal New Russia. London: Guardian Faber Publishing.

Harris, K. (2020). ‘Russia’s Fifth Column: The Influence of the Night Wolves Motorcycle Club’, 43, 4: 259–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1455373

Hutchinson, S., and O’Malley, P. (2007). ‘A Crime-Terror Nexus? Thinking on Some of the Links between Terrorism and Criminality’, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 30, 12: 1095–107. DOI: 10.1080/10576100701670870

Jnr, T.E.D. (1978). ‘An Analysis of Weber’s Work on Charisma’, British Journal of Sociology, 29, 1: 83–93.

Jupp, J., and Garrod, M. (2019). ‘Legacies of the Troubles: The Links between Organized Crime and Terrorism in Northern Ireland’, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 45, 5–6: 1–40. https://doi-org.ezproxy.wlv.ac.uk/10.1080/1057610X.2019.1678878

Kelly, M.K. (2017). The Crime of Nationalism: Britain, Palestine, and Nation-Building on the Fringe of Empire. 1st edn. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kerr, S. (2022) Wealthy Russians flock to Dubai as west tightens sanctions, The Financial Times, March 10th. https://www.ft.com/content/d6d3b45a-35cc-4e32-b864-b9c0b1649a79

Magyar, B. (2016). Post-Communist Mafia State: The Case of Hungary. 1st edn. Hungary: Central European University Press.

Roth, M.P., and Sever, M. (2007). ‘The Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) as Criminal Syndicate: Funding Terrorism through Organized Crime, A Case Study’, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 30, 10: 901–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100701558620

Silke, A. (1999). ‘Rebel’s Dilemma: The Changing Relationship between the IRA, Sinn Féin and Paramilitary Vigilantism in Northern Ireland’, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 11, 1: 55–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546559908427495

Tupman, W.A. (1998), Where Has All the Money Gone? The IRA as a Profit‐making Concern”, Journal of Money Laundering Control, 1(4). 303-311. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb027153

Weber, M. (1968) Economy and Society, Roth and Wittich, eds. New York, Bedminster Press.

Wright, A. (2005). Organised Crime. Cullompton: Willan.

0 Comments